Please Have A Seat

‘Please have a seat’ was on display at Artisans’ Centre gallery, Kalaghoda, between the 22nd April and 4th May 2016.

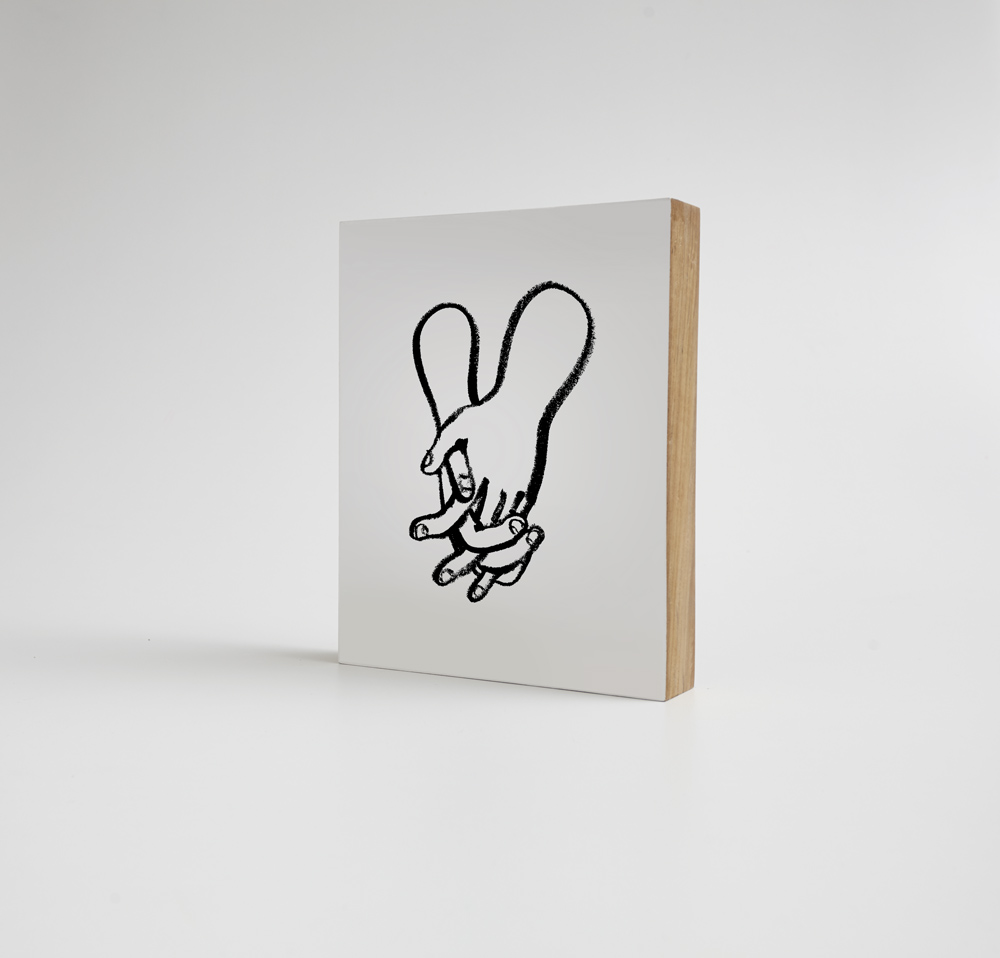

All works in the show were screenprinted (reproductions of original drawings) on acrylic and wood. Original drawings were selected from sketchbooks between 2013-2016.

Scroll to bottom of page for an essay by Phalguni Desai.

The sum of all our parts.

In our over-photographed, selfie every time you turn, CCTV here, security cameras there kind of times, its funny to think of a sketch as more potent proof, but let’s face it, even in 4k image resolutions, it’s easy to miss the details that imply a more personal story than clothes and accessories and makeup. Caught up in decoding exteriors, we do end up missing out in this overwhelming series of moments is the physical language of being humans.

Sameer Kulavoor is many things at once: professionally, he is a designer. Most other times, he’s a traveller, a guy with a sketchbook lurking at the corner table of your neighbourhood cafe chain. This other life of Kulavoor isn’t so well known except perhaps to those who follow his Instagram (fellow designers, art students who look at him for inspiration, people who know him from his ‘commercial’ venture BombayDuck Designs). Sameer is also what I call a compulsive sketcher. At the moment, he is also an artist marking his first solo exhibition, Please Have a Seat. The exhibition features a series of drawings that are part travelogue, part meditation on what it is to be, in moments of rest or contemplation. Stripped to minimal lines of a solid marker and blown up as large screenprints on paper, wood and acrylic, these images are at once comforting in their anonymity and disturbing when you think of the intimacy they imply.

Without a lens to go closer, or a camera to hold still while taking a sneaky photo of an interesting-looking stranger, Sameer bypasses some details for others. The suite of drawings in the show function like repositories for actions, moods and the passage of time as Sameer’s seemingly uncomplicated images. A man lays horizontal playing with his phone – but he’s hardly at home, he’s whiling away time on a sleeper berth of a train on its way to Chennai. Two women you think you know have coffee together in a cafe you’re sure know (but it’s probably not the one you thought it was). Hands of a squatting man, elbow up. You know he’s squatting not because you imagined the title, but rather because you saw the pressure lines where his knees should be. The title says he’s watching cricket, but he could also be chilling under a tree, chewing the fat. Whether he is old, young or going through a midlife crisis is up to how far your imagination can go.

Where these moments take us, however, is not entirely under debate. Some take me back to Arun Kolatkar’s Kalaghoda Poems, or city-based painter Sudhir Patwardhan’s work from the nineties. Slice-of- life images. The good, the bad, the cringeworthy all presented together as a fact of life, infused with dry wit and humour, showing the audience something without letting them judge it too harsh. Sameers drawings seem a bite of the slice of life Patwardhan and Kolatkar serve us. They remind us of the little things that we rarely notice until they’re large enough, like the beginnings of a wrinkle, the makings of a friendship, the birth of an idea. These happenings, which begin in the quiet of the mind are made loud in these offerings.

They also, to my mind, highlight the quintessential ‘Bombay’ness of Kulavoor, who began sketching his neighbourhood in Mumbai’s northern suburb of Borivili well before contemplating art school. There’s something unapologetic in the way he looks at people as a sum of many, many parts; something that reminds me of being pressed in a Mumbai local against far too many body parts with almost no complaints. The way someone’s sweat becomes fact of life that shows up on your way to work, in these drawings, texture, colour, shape, all become facts of life, inconsequential till our gaze wonders about the hundred possibilities each image creates.

Phalguni Desai (art writer and critic)

All images and site content copyright ©️ 2010-2022 Sameer Kulavoor.